A gearbox manufacturer is crosschecking its products to ensure that they have not been placed under undue load by turbine makers.

Winergy Drive Systems, a leading gearbox maker in the industry, has launched a research project that may help deflect some of the blame regularly levelled at gearbox manufacturers for failures and poor reliability. Gearboxes of all makes, in all makes of host turbine, are widely considered the weak point of a machine, often failing to outlast other critical components during the turbine's two-decade lifespan. Although the probe is done in partnership with Winergy's customers, there are fears that it could have repercussions elsewhere in the sector (see box).

Winergy will crosscheck the force being thrust on to its gearboxes in operating wind turbines against the original specifications provided by turbine manufacturers in the design phase of the turbine. Experts say that if Winergy can show that wind turbine gearboxes are experiencing forces that surpass those provided in the original design, Winergy can mitigate some responsibility for what is generally seen as sub-par reliability.

"Gearboxes have failed at higher than expected rates," says Sandy Butterfield, a former chief wind turbine engineer at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory in Colorado, where he led a research project on gearbox reliability. "These are supposed to be 20-year designs and many know that we're not getting 20 years from them."

It is hard to quantify how often gearboxes fail, he says, because there are few statistics or studies available. Generally, the wind industry expects today's gearboxes to last 7-11 years, but this can vary either way. "I've seen 750kW machines fail every three years," Butterfield says. "Clearly, the new fleet is doing better than that but the jury won't know until they've been out there another five or ten years."

Varying loads on rotors and drive trains, such as torque and bending forces, are the prime suspects in degrading gearbox life span. The capacity factor - the percentage of maximum output achieved by the plant over the course of a year - and the nature of wind regimes at certain sites dictate the severity of the loads. "Rarely do we go back to a specific wind farm and validate the loads that the wind farm or that particular machine match those that the turbine is designed for," says Butterfield. "One thing that could be done is to go ahead and verify those loads."

Test turbine

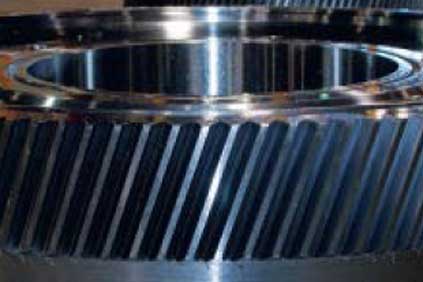

Winergy's project will measure the operational loads and check them against original design specifications from the manufacturer. By this month, it expects to have an operational wind turbine in Europe fitted with strain gauges and other sensors. The company can then compare the loads that are being delivered to various parts of the gearbox in a real-world situation and compare those to the original design specifications given by the wind turbine original equipment manufacturer (OEM).

During a turbine design phase, OEMs have multiple programmes for simulating load on the blades, main shaft and gearbox of a turbine. "Basically, we design the gearbox to the loads the OEM has supplied and how much space is available in the tower and weight restrictions," says Eckart Bodenbach, an engineer at Winergy. "Once the gearbox is supplied, nobody goes back to determine if the loads that were initially given to the designer of the gearbox are the loads that are actually being experienced. That's why at Winergy we have started this load-monitoring system that we are testing now."

The Winergy project may have legal as well as technical implications, say wind experts

There is widespread suspicion that the forces that gearboxes, rotors and drive trains experience in the field are higher and more variable than original design parameters account for, leading to premature wear and failure. In an age of lawsuits, liabilities and warranty claims, gearbox manufacturers, tired of the accusations that gearboxes are the Achilles' heel of wind turbines, are eager to repel some of the blame if data backs them up.

There is some surprise that this type of crosschecking is not already an established procedure. "There's a big difference between what the engineer crunching numbers expects and what the turbine in the field experiences," says David Crowley, director of technology development for Standard Aero Technical Services, a firm entering the wind turbine service market.

.png)

.png)