Last month, French startup Lhyfe officially kicked off construction of a wind-powered green hydrogen plant in Port du Bec in the Loire-Atlantique region.

But while most green hydrogen projects are looking to offshore wind, Lhyfeâs facility on a windy stretch on Franceâs western coast near Nantes will be connected to three of the eight turbines at the Bouin onshore wind farm to produce 300kg of electrolytic hydrogen a day from next spring.

The hydrogen will be transported by truck â hydrogen-fuelled, of course â to the nearby town of La Roche-sur-Yon to power newly-converted hydrogen buses and refuse trucks. A research centre will be built next door to improve the technology and develop it offshore.

âThis will be a world-first on an industrial scale â 300kg of hydrogen is equivalent to the consumption of 700 cars,â said Lhyfe founder Matthieu Guesné.

âTo extract it, you donât need to pump a lot of water since you get the same amount of energy in hydrogen from one litre of water as you do with one litre of petrol. Itâs almost magical.â

Guesné chose the Bouin wind farm (below) after meeting Alain LeBÅuf, head of the renewable energy industry organisation of the Vendée region in France, where Lhyfe was set up, in 2017. âHydrogen is the energy of the future, itâs plentiful and completely recyclable,â said LeBÅuf.

âWe needed to make the most of the fact wind wasnât expensive to try out this experiment,â said Leboeuf. The wind farm was reaching the end of its support period at the time.

Modular concept

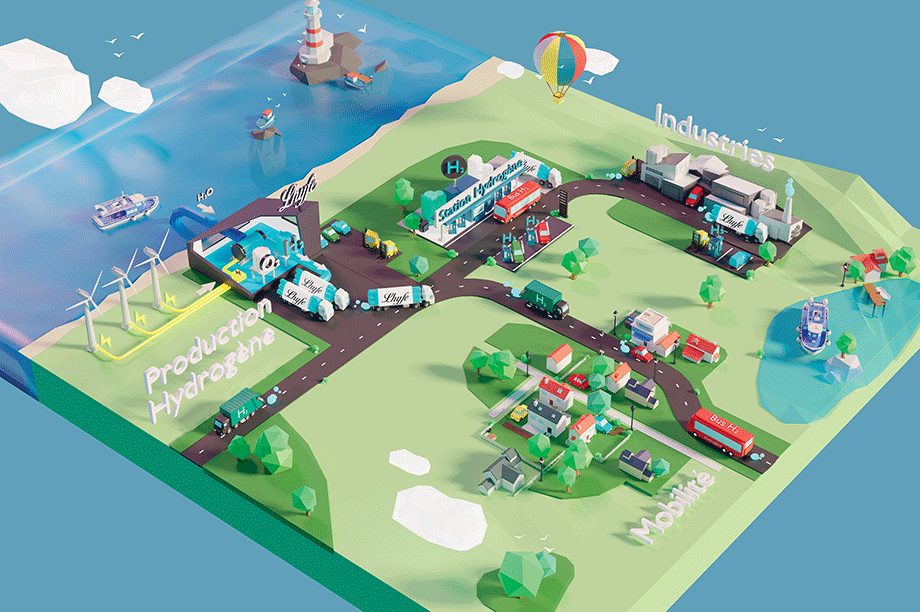

Lhyfeâs aim is to deploy green hydrogen plants anywhere for local use. The companyâs units are modular and can be assembled next to any source of renewable power, including wind, solar, biomass, biogas and geothermal. The fuel is transported by road, eliminating the need for electricity cables or pipelines.

The concept is drawing attention nationwide and further afield. Only three years after it was founded in 2017, Lhyfe has 40 projects in the pipeline and recently signed a framework agreement with Norway-based hydrogen company NEL. It has opened a subsidiary in Germany and plans to have representatives in Spain, Italy, Portugal and Northern Europe by the end of the year.

The next stage for Lhyfe is to experiment offshore, with plans to build units next to offshore wind turbines 50km off the coast. A 1:100 scale demonstrator is planned off the coast of Saint Nazaire for 2022, followed by the first "real" offshore green hydrogen plant in 2024 or 2025 , for which the company is yet to decide on a wind project.

Offshore obstacles

But this technology still faces a number of challenges.

âElectrolysers will have to be much more powerful than they are today if they are to be used offshore, with at least 100MW or more,â explained Guénaël Le Solliec, energy and transport engineer and R&D manager at the CEA public energy research centre in Nantes, which is collaborating with Lhyfe.

Other issues associated with being off the grid could be impacts on power electronics and managing electrons as well as challenges from the harsh marine conditions on equipment, logistics and lifespan of these units, Le Solliec said.

Guesné is cautious. âTo this day, no electrolyser has worked out at sea, itâs unchartered territory. Weâre not the only ones trying to work it out, thereâs fierce competition to see who will get there first,â he said.

Indeed, various projects have been announced in recent years, some involving major wind industry players.

In Denmark, Ãrsted and five other multinationals have teamed up to build what has been touted as the worldâs largest green hydrogen offshore facility in the Baltic Sea. The partners hope to produce more than 250,000 tonnes of clean hydrogen per year by 2030.

Meanwhile, developer ERM is working with hydrogen specialist NEL and South Korean technology conglomerate Doosan on its Dolphyn project in Scotland, planned on floating wind turbines off the coast of Kincardine, with the goal of having a 400-turbine field with a capacity of 4GW by 2032. A 2MW prototype is planned for 2024, followed by a 10MW full-scale pre-commercial facility for 2027.

Spanish power giant Iberdrola recently set up a hydrogen unit and is looking at projects in the UK and Spain.

These are promising times for hydrogen in Europe as long as the right policies are in place, said Guesné.

âEurope is in the race to be a green hydrogen champion,â he said. âBut itâs important to put the money in the right place, especially on the production side. We would much rather have customers than subsidies.â

All eyes on hydrogen

Hydrogen is set to become a major asset in the fight against the climate emergency. The gas is widely used in industry, emits no CO2 when burnt and is light, energy-dense and very versatile. It can be used as a fuel, for storing and carrying energy and could be expanded out to transport and buildings âsectors that are difficult to decarbonise. However, the bulk of hydrogen today is supplied from fossil fuels and very carbon-intensive.

With renewables and electrolysers getting cheaper, producing green hydrogen is becoming more viable. As governments scramble to find ways to balance increasing energy demands with the need to drastically cut back on greenhouse gas emissions, global interest in the clean gas has surged.

Hydrogen is a cornerstone of the EUâs Green Deal announced in July, which set the goal of producing up to 10 million tonnes of renewable hydrogen by 2030. To scale up production, the European Commission has launched the European Alliance for Clean Hydrogen, comprising companies, governments and industry experts.

On a national level, ambitious hydrogen plans have recently been announced in Germany, Portugal, France and Spain, each with funding of â¬7-9 billion.

Another indicator of the green hydrogen boom is the rising demand for electrolysers, used for splitting water into hydrogen and oxygen. Installed electrolyser capacity worldwide reached more than 25MW in 2019 â from less than 1MW in 2010, according to the International Energy Agency. The EU has set a target of 40GW of renewable hydrogen production by 2040.

By 2050, green hydrogen could translate into 8% of global energy consumption, with 16% of all generated electricity used to produce hydrogen by then, according to a 2019 Irena report.

This could bring economic benefits too: In the UK alone, green hydrogen could be worth £320 billion (â¬351 billion) and support 120,000 jobs by the middle of the decade, a report published last month by the Offshore Wind Industries Council and ORE Catapult concluded.

.png)

.png)