Update: Vineyard committed to the project on an adjusted timescale, but did not offer details. BOEM confirmed it would publish a supplemental environmental impact statement by the end of 2019 or early 2020. The article below has been amended accordingly.

Vineyard needs a final environmental impact statement (FEIS) from the US government's Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) to proceed.

It had been expected in April, before BOEM declared in June it would carry out another review into the project.

Now, in a surprise announcement, BOEM said it would expand the review to include other wind projects in the region with power purchase agreements (PPAs).

Ørsted and Eversource's 130MW South Fork and 704MW Revolution, both off Rhode Island, have PPAs.

"The federal government's decision to further delay the approval of the FEIS for the Vineyard Wind 1 project comes as a surprise and disappointment," said Vineyard in a statement.

"While we appreciate that the discussion on cumulative impacts is driven by rapid growth of the industry beyond our project, we urge the federal government to complete the review of Vineyard Wind 1 as quickly as possible."

Timeline

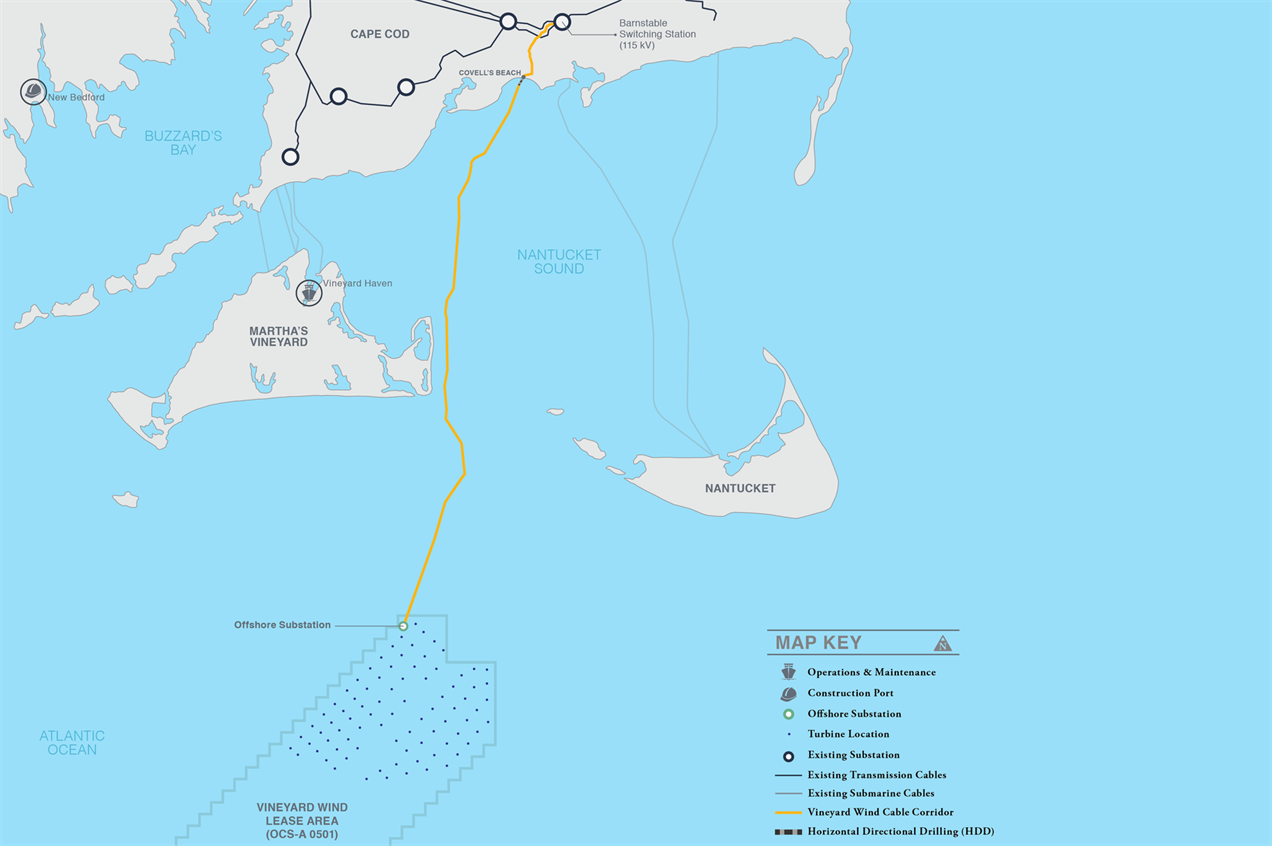

Concerns about fishing are holding up Vineyard Wind, off Massachusetts, set to become the US's first commercial-scale offshore wind project.

Vineyard was already on a tight timetable and is contracted to deliver electricity starting in February 2022.

As a result of the review, the full project could fail to start construction this year in time to be eligible for a 24% investment tax credit (ITC).

On 12 August, Vineyard confirmed that the original timetable is now unfeasible, but it did not offer details.

The $2.8 billion project is a joint venture between Avangrid and Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners.

With several other major projects planned in the near-term off the north-eastern US, the delay is being closely watched.

The two-phase Vineyard Wind is considered a bellwether for the industry in the region, which could see more than 18GW of installed capacity by 2030.

Another federal agency, the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), had already refused to endorse BOEM's draft EIS for Vineyard, saying the fishing industry's concerns were not fully addressed.

American Wind Energy Association CEO Tom Kiernan called the decision to delay the project was "regrettable".

"[It] undermines the Trump administration's American energy dominance agenda and a major US economic growth opportunity," he said.

Vineyard Wind had already piled the pressure on BOEM.

The company had warned that it would be "very challenging" to move forward with the first 400MW phase of the project in its current configuration if the FEIS has not issued been by mid- to late August.

"Having said that, it doesn't mean the project is dead by any stretch, it just means we're going to have to reconfigure things or do something differently," Avangrid CEO James Torgerson told financial analysts in late July.

BOEM said it hoped to publish a supplemental environmental impact statement by the end of 2019 or early 2020.

Concerns

Fishermen object to Vineyard's spacing of the turbines, originally at 1.4km apart, arguing it is too tight. They have called for a spacing of 1.9km between the turbines.

Nor do they like the orientation of the rows of turbines, from north-west to south-east, which they say is at odds with their traditional east-west routes.

Vineyard Wind released a graphic detailing the planned distance between turbines at the project

In response, Vineyard moved the planned location of three of the turbines, and agreed to widen the transit corridors in future projects. However, fishermen remain unhappy.

The developer has also reduced the total area of turbine sites by some 23% by using a larger 9.5MW turbine model, which reduces the number of turbines from 108 to 84.

Wes Brighton, a fisherman and board president of the local Martha's Vineyard Fishermen's Preservation Trust, said he remains concerned about the environmental footprint of the project, including potential impacts of transmission lines on fish migration and pile-driving on endangered Right whales.

"To see [the environment] sacrificed for something that will have such as small impact on climate change is disheartening," he said, adding that he would not oppose all wind projects.

'Dangerous moment'

Any delay for Vineyard is significant, according to Anthony Logan, senior wind analyst at Wood Mackenzie Power & Renewables.

"The project is really far along — it's kind of a dangerous moment. The contracts have been signed. Financing should be just about wrapped up. You don't want this hanging over your head."

Even before BOEM's latest delay, commercial fishermen had been vociferously questioning plans for other wind projects off New England because of what they say is a potential loss of fishing, and unknown impacts on fish migration and the sea floor.

They argue that the experience in the North Sea, where the offshore wind sector has been growing for 20 years, is not necessarily relevant as the fish and shellfish species are different and North Sea fishermen tend not to fish with mobile trawl gear, said Brighton.

Besides, North Sea wind projects started much smaller and developers have only recently started building sites hundred megawatts in size.

.png)

HR.jpeg)

.png)