In the early years of offshore-wind development, most projects were characterised by modest turbine numbers of 2-3.6MW capacity, typically located 5-30 kilometres from shore.

As a single-journey sailing time of 60 to 90 minutes is considered the practical and economic maximum, such projects could be serviced from onshore facilities with fast crew-transport vessels.

The sector has changed rapidly over recent years, however. Turbine capacity expanded into the 3.0-6.2MW range, and is now pushing towards 8MW and beyond, while the average size of projects has grown, with developments of 400-700MW increasingly common.

A parallel trend has been to construct these large-scale projects much further from shore.

Helgoland airport - a 480-metre airstrip suitable only for small aircraft - is situated at Dune, the smaller of the archipelago's two islands, linked to the main island by a ferry.

This is where utility E.on has established a service hub to carry out and oversee maintenance work at the Amrumbank West offshore project.

Located nearly 100km north-west of the German North-Sea port of Cuxhaven, Amrumbank West is a good example of the trends in offshore development outlined above.

It was commissioned in late 2015 as a 288MW project with power provided by 80 Siemens SWT-3.6-120 turbines. Capacity has since grown to 301MW with the installation of a software-based power boost function activated by wind speeds of 13-19m/s.

Measured against 301MW, and 3.76MW with power boost on, the project is calculated for 4,296 full load hours (a capacity factor of 49%), and annual generation of 1,229GWh.

Smart logistics

Inside the new service, logistics and support building, a team of engineers and technicians continuously monitor Amrumbank West's operational performance.

A range of spare parts, equipment, working gear, and protective clothing is stored in another part of the building, while a helicopter is kept on standby in an adjoining, sheltered area.

Amrumbank West production manager David Teichert explains the importance of the hub's position. "The distance between Helgoland and Amrumbank West is only 39km, and roughly 62km between Helgoland and Cuxhaven," he says.

"So Helgoland's geographic location makes it the ideal offshore platform for us. The wind farm's availability has been close to 98% from the very beginning, but year-round turbine accessibility at such a remote location remains a challenge and requires smart logistics.

"For Amrumbank West we chose a combination of two to four chartered Swath-type crew transfer vessels, plus helicopter deployment for when time is urgent and it is above 1.5-metre significant wave heights."

Swath (small water plane area twin hull) vessels are characterised by their two submarine-shaped hulls that are submerged during sailing.

The distance between these hulls and the ship deck incorporating service personnel accommodation is covered by rather narrow vertical columns with a minimised surface area.

Swath-type vessels are known for their stable sailing performance in high waves and rough weather, especially compared with conventional single-hull service vessels.

According to Teichert, Swath vessel sailing speed is 17-20 knots, so each journey from Helgoland to the wind project takes an average of 60 to 90 minutes, although this depends on a number of variables, including wind speed.

The helicopter flight permit is for a maximum of 300 combined starts and landings a year. Each potential deployment must therefore be weighed carefully for associated downtime, overall costs and possible alternatives.

Joint staff

A mixed service team for wind project upkeep is now a common model for Siemens, according to a spokesperson for the manufacturer, so Siemens and E.on service staff share offices in E.on's hub building.

Amrumbank West also uses a two-shift service team system, with each 12-strong crew working a 14-day on/off schedule. Crew change and supply chain activities between Helogland and the mainland normally use the regular ferry service.

During their two-week working shift, the team, always comprising six Siemens and six E.on technicians, is stationed on Helgoland. The same mixed-team approach is applied to the staff responsible for remote turbine monitoring.

"In future we might expand the mixed-staff service model to sharing personnel between neighbouring wind farms of different ownership but all using the same turbine model," says Teichert.

"The key for such decisions is that they should always contribute positively to better availability, higher annual energy production, and, ultimately, towards lowering the levelised cost of energy."

Energy islands

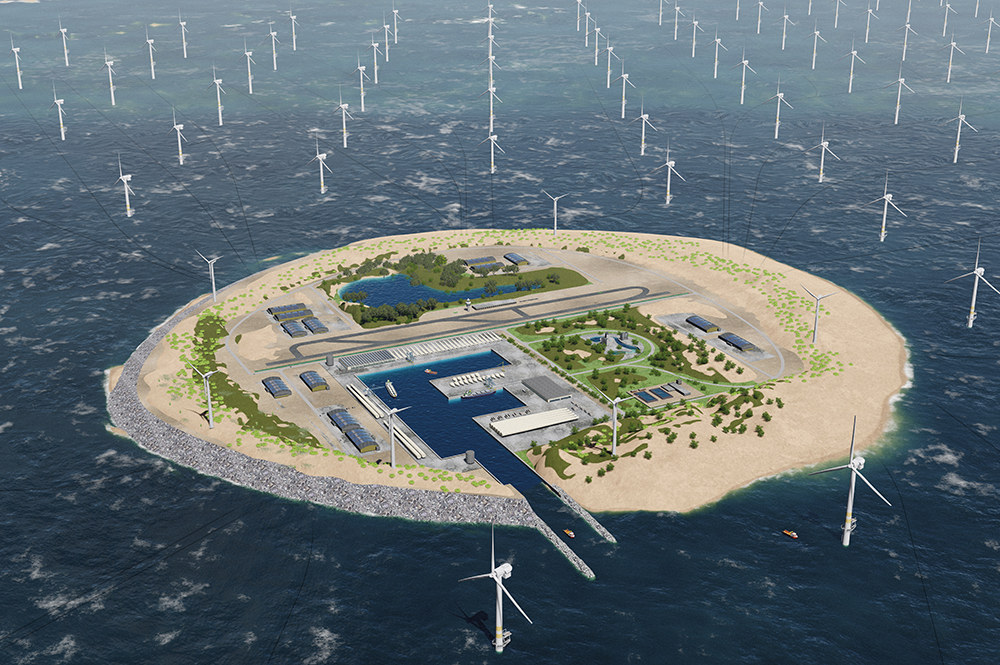

An early plan for an integrated energy island was presented in 2007 by Dutch organisations KEMA (now DNV GL), engineering consultancy Lievense (now LievenseCSO), and "futurist designers", the Das brothers. The main principle outlined in their feasibility study is a pumped energy storage (PES) plant designed as a "falling water-column lake".

The energy island would basically consist of a sealed-off ring dyke enclosing a water surface area of around 60 square kilometres, and the lake would be 32-40 metres deep.

During electricity surplus situations, water is pumped out of the lake; when there's a shortage, water is allowed to fall back into the lake. This time it drives the dual-mode motor/generator electric machine in generator mode.

Dutch energy-island pioneer Chris Westra was closely involved with this study. He explains that the developers envisaged adding multiple functions to the PES plant, including a construction and assembly, harbour and service hub for offshore wind projects.

A year later Westra introduced another futuristic concept for an artificial energy island, envisaging three potential North Sea locations for the Dutch coast. The concept was developed in cooperation with Lievense, and the construction costs were estimated at €750 million.

Transmission system operator Tennet recently unveiled its own vision for a hub-and-spoke transmission solution in the form of an artificial island in the Dogger Bank area off the UK's east coast. Westra says: "I am really pleased with Tennet's plans as presented in their concept outline.

"In my view, multiple service island hubs will be necessary to enable the envisaged huge future growth of offshore wind power. They can provide sufficient space for service-personnel accommodation, harbour facilities and the required electrical infrastructure."

Westra adds that the current expensive jacket support structures for transformer and converter stations could be eliminated, while the service-hub-island concept offers a sound basis for attracting investment finance.

The concept has huge potential for further innovations and expanding functions beyond the ideas currently being explored,he believes.

In 2014, the Belgian government passed a law allowing the construction of an artificial island in the North Sea, to be built 3km off the coast near Wenduine, north of Brugge. The facility would serve as a day/night storage buffer for multiple offshore wind projects with a total rated capacity of 2.8GW.

Growing interest

The operating principle is again a PES plant designed as a falling water column lake. The construction costs are estimated at €1-1.5 billion. The Belgian island concept has also attracted the attention of German project developers, who would be likely to add wind-project servicing functionalities to the hub.

Opinions over the value of artificial islands have changed rapidly in recent years. A 2010 survey conducted among international offshore-wind industry experts asked for their opinions and preferences on three alternative marine hotel/service options.

The first was a permanent man-made island with harbour facilities servicing multiple wind projects. The second and third options were a floating hotel/service vessel, and a jack-up type hotel/service barge, both aimed at serving a single wind farm.

Most participants at that time gave their lowest ranking to the permanent island due to its envisaged cost and perceived lack of flexibility.

While support for the concept has increased, an actual artificial offshore-wind service island has yet to be built, and will no doubt face many uncertainties, ranging from attracting the required capital and dealing with unexpected technical and legal risks.

Competition, meanwhile, comes from innovative alternative solutions developed by the shipping industry. These include floating hotel vessels with incorporated workshops, parts storage and helicopter landing decks.

Conceptually different variants at least partly filling similar functions are the fitting of existing jack-up vessels with hotel facilities, or developing new dedicated solutions such as the Damen accommodation unit. But most important is that each solution must be optimally adapted for its envisaged main tasks and functions for the lowest possible lifecycle costs to the owners and operators.

The Helgoland press trip was organised by Hamburg Messe in advance of WindEnergy Hamburg, which takes place 27-30 September.

.png)

.png)