But there is concern whether the new process will bring projects to fruition any quicker, and not enough capacity is planned to help the sector grow.

The offshore wind industry has called on the French government to offer greater visibility and sufficient volumes as the only way to realistically bring down costs.

The last two tenders date from 2011 and 2013, when nearly 3GW was allocated. In April, energy minister Segolene Royal announced a third round offering a single zone off Dunkirk.

There is no clarity beyond that, however, apart from a broad target of up to an additional 6GW allocated in 2023 for fixed-foundation turbines and up to 2.1GW for marine renewables, including floating wind. In the meantime, France's fledging offshore sector is struggling to get off the ground.

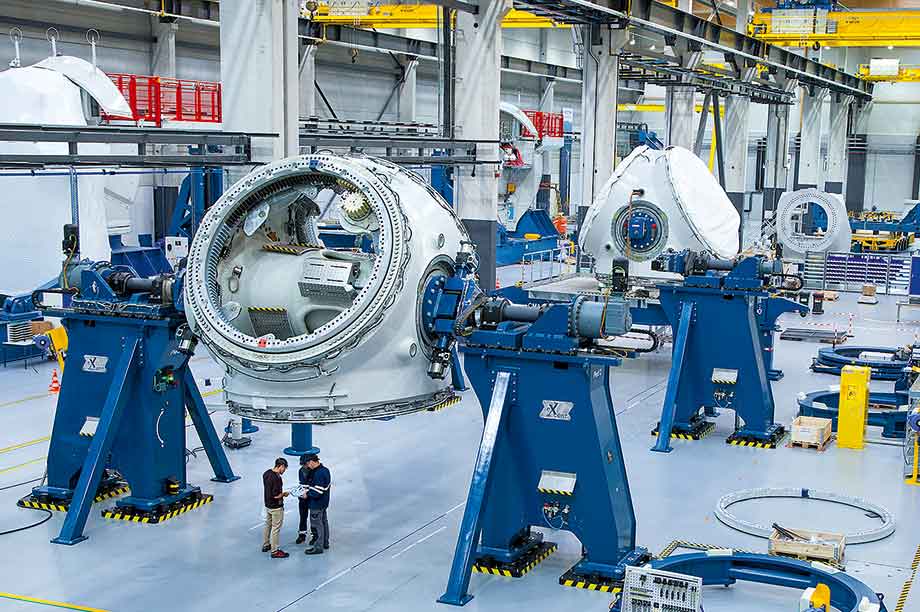

The recent merger of Gamesa and Siemens has put a question mark over the future of Gamesa-Areva offshore joint venture Adwen, which has undertaken to build factories at Le Havre. GE Renewable Energy is holding back on plans to build tower and blade factories in Cherbourg for its Haliade 6MW machine.

"We need firm orders before making the final investment decision," said Nicolas Serrie, global account executive at GE, referring to the fact that France's first-round projects are still going through the permitting process. Serrie was among the speakers at a recent Seanergy conference in Biarritz. All being well, GE will supply three projects with 238 Haliade turbines.

Speakers at Biarritz welcomed the third tender, but called on the government to increase capacity. Dunkirk is likely to be 500MW at most, while the minimum required to drive costs down is three zones of 2GW in total, said Jean-Louis Bal, president of renewable-energy trade association SER.

And cost is crucial: the additional 6GW is conditional on price, acceptability and feedback from the first projects, the government says. As speakers kept repeating, the main criteria for driving down costs are, of course, visibility and volume.

All change

To help speed up deployment, encourage competition and reduce costs, the third tender will be run under a new system, based broadly on the Danish and Dutch models. While the framework is still under discussion, the basic structure has been announced - to some criticism from energy regulator CRE (see box).

The new procedure will be one of "competitive dialogue", allowing discussions with pre-selected candidates before the terms are finalised and the main tender is launched.

This will enable developers to refine their bids and allows more flexibility, unlike previous rounds, where almost everything, including the turbine supplier, had to be decided in advance. Among other things, this made it difficult to benefit from technical improvements and introduce competition between suppliers.

The state will also undertake "derisking studies", including wind measurements and geophysical investigations. Nevertheless, several important studies will be left to selected candidates, including impact assessment and geotechnical and grid connection analysis.

"This is partly a question of time," explained Antoine Decout, head of marine renewables at SER. "Developers were eager that the tender goes ahead quickly, so this is a compromise."

Meanwhile, the industry is pushing the state to provide the scope and quality of data required. "If the results are less than 100%, it will cost more in the long run if developers have to start again," noted Philippe Kavafyan, SER's president of offshore wind.

The first two rounds were decided on the basis of price (40 points); industrial plans (40); and environmental issues and acceptability (20) in order to establish a manufacturing base. It is likely the next round will allocate more than 50 points to price and fewer to the industrial component.

But some argue that price alone should be the deciding factor in order to really drive down costs and encourage competition. Others insist the industrial sector still needs support.

The expected timetable foresees the pre-selection process and derisking studies starting this summer, followed by at least three months of discussions before the tender terms are finalised. The deadline for bids is likely to be late 2017.

The winners will receive permission to occupy the maritime domain, but still have to secure authorisations under environmental law. This will not only take time but also introduces more uncertainty, both of which increase costs.

A question of time

As a result, some worry that the new procedure might not actually be any faster in the long run. "If we have to wait one or two years while the state completes the studies, the result will be negative," argued Beatrice Buffon, executive vice president of marine renewable energies at EDF Energies Nouvelles.

GE's Serrie agreed. "The process must be coherent with the aim to reduce costs. If it takes longer, costs will increase," he said.

While the government has simplified the permitting process to some extent, for example revising the appeals procedure, they could do more, the industry argues. The government needs to set up a high-level management team "which can advance on all subjects at the same time: planning, legal issues, tenders, etc", Buffon said.

A single point of contact would also help, rather than developers having to do the rounds of the different offices, which are not always consistent.

Improving public acceptability is also crucial. This will be helped in the longer term by establishing a maritime spatial plan, defining which activities can be conducted where, explained Catherine Chabaud, the ministerial delegate in charge of drawing up the plan.

The first working group, comprising all interested parties, took place in June, although the final plan will not be ready before 2018, Chabaud said.

Another key element is to improve visibility by having "a sequential process with serial tendering", Kavafyan said, pointing to the Dutch model, where 700MW will be tendered annually over the next five years.

"If the gap is too long before the next tender, it is a risk for industry and employment," Buffon warned. It will also have an impact on cost.

"To encourage competition you need confidence and visibility on volume so that investors engage," noted Silke Ehrhart, project manager at RES.

The industry believes EUR100-120/MWh, including grid connection, is achievable for projects commissioned in 2030, compared with an average of EUR200 in the first two rounds. But that is assuming 15GW installed capacity in 2030 - which brings us back to visibility and volume.

REGULATOR SLAMS TENDER PROCESS

The new process of "competitive dialogue" proposed by the government is "inadequate" when it comes to sharing risk between the state and candidates and ensuring sufficient competition, French energy regulator CRE said in a report issued in late May.

Indeed, the process might actually lead to less competition because only pre-selected candidates can bid in the main tender, CRE warns.

More should be done to ensure the maximum number of developers enter the pre-qualification phase, for example by publishing the draft tender terms early on and giving candidates at least six months to apply.

CRE also recommends allowing greater flexibility in the bidding process. In the first two rounds, projects have to conform exactly to the description given in the application. This introduced a strong constraint on technical choices before the various studies had been completed.

Instead, the tender terms should simply "define the obligations to be met by candidates and the conditions under which projects can evolve, including permitted modifications and any necessary authorisations", the report says.

This would also allow the developers to take into account issues raised during the required public consultations and in turn help improve acceptability.

.png)

.png)