Not only does this section support the entire tower or platform, but it is where the crucial connector cables are situated. Without these connections, any power generated goes nowhere and revenue is lost.

The three main sub-surface issues that need to be considered are: physical damage (including coating damage), corrosion and seabed scour. As the scale of offshore wind farms continues to grow, it becomes ever more important that we learn from across the wider offshore industry to effectively tackle these key subsea issues. One approach is to develop a rolling operations and maintenance (O&M) programme that incorporates regular subsea inspections and rapid response plans.

The offshore oil and gas industries have learned this lesson over a long period of time. Originally very little was known and understood about offshore operations, so it was a relatively unregulated area. However, operators soon began to discover that the sections that lay beneath the water were beset with problems, many of which could have been prevented by regular inspections. This led most operators of the time to start annual inspection programmes to control and preserve subsea structures, even before regulatory requirements came into practice in the 1970s. This experience can easily be transferred to offshore wind projects, where the structures themselves are generally less complex than in an oil or gas field.

Inspections

Inspecting offshore wind farms, and in particular their subsea components, is not a complex task. There are a number of possible methods to effectively execute an inspection, including the use of a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) and a multibeam bathymetry system mounted to the survey vessel. The bathymetry system provides a map of the seabed allowing imaging of scour, debris and other features. The ROV can then be used to directly visualise the structure itself and can also serve as a platform to obtain cathodic protection readings, which, together with visual inspections provide an indication of the level of corrosion and physical damage that may be present. Though the data obtained from these systems can be complex, it is easily interpreted and understood.

The bathymetric map may be used to assess the level of scour present around the foundation and the effect this has on cable entry into J-tubes or the piles themselves. Regular inspections are recommended to determine the rate of change. This is particularly important where scour may be in the early stages of development as this is the time to act. Once scour starts to develop, it can spread rapidly and can have a detrimental effect on key components.

Some have questioned whether scour pits at the base of a foundation are cause for concern. They most certainly are. Power and control cables are protected by various types of bend-restricting systems, but such systems are of finite length and are also affected by wear and tear, especially as the currents around the base of the tower are constantly moving.

As a scour pit develops, the potential for mechanical movement of a cable at its interface to the tower increases and this, in turn, increases the rate of wear on the cable, potentially leading to a breakdown. With the right O&M programme this can be easily prevented.

Preventive action

Conducting an O&M campaign does, of course, incur a cost. However the cost of not conducting a survey and understanding the condition of the asset may be significantly greater. Arguably, a cable fault not only leads to a loss of power generation and revenue but also to a significant repair cost that far outweighs the cost of installing a number of basic protection and maintenance measures, either at the installation phase or following a regular inspection programme.

A regular inspection programme is therefore seen to de-risk an operational wind project while prolonging its anticipated lifespan. But how regularly should an inspection programme take place? Unfortunately, there is no definitive answer, but any programme should definitely take into account the local site conditions. With wind farms traditionally being built in areas with high currents, the opportunity for scour is ever present. When constructing a wind project, a baseline survey should be undertaken at the earliest opportunity after the subsea structures have been installed. Thereafter it would not be unreasonable to conduct a survey a year later to compare with the baseline. The difference in datasets will indicate whether or not annual surveys are sufficiently frequent.

There are various solutions available to combat the effects of scour; from rock dumping to the installation of concrete protection mattresses, eco-friendly rock bags, fronded mattresses and recycled tyre mattresses. Each of these solutions has its pros and cons.

Expensive rocks

Rock dumping is a coarse and expensive solution. It may be used to fill scour pits and bury exposed assets, but it requires a potentially expensive rock dumping vessel to deploy large volumes of rock. Deployment is often monitored in real time from the surface to ensure the rock lands exactly where it is needed. Although some national organisations have been reluctant to approve rock dumping in the past, it does create a reef like structure, which improves marine habitat.

Rock bags are a relatively new solution to the problem. They have developed from simple net-like bags filled with rock to more eco-friendly fibrous bags filled with sand or various sizes of aggregate. These bags have the added advantage of disrupting water flow and encouraging sediment deposition as they are made from a geotextile material.

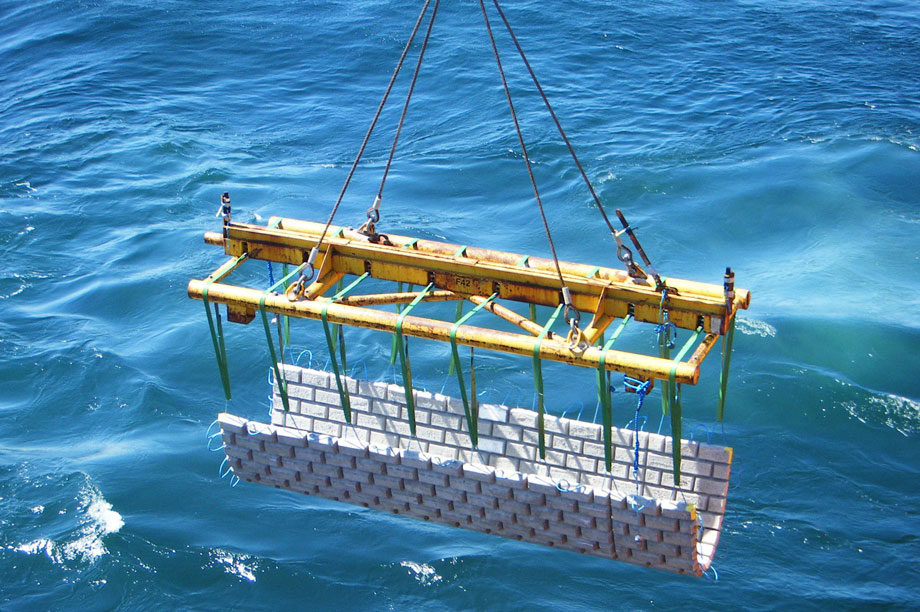

Perhaps the most favoured protection comes in the form of concrete protection mattresses. These are created from interlinked concrete blocks that conform to a subsea surface and provide a hard cover over any softer sediments which cannot then be eroded by scour. This system is widely available and has been in successful use for a number of decades. Mattresses are typically installed using a dedicated lifting frame that can be positioned from the installation vessel.

Fronded mattresses are available in two basic variations. In the simplest form these are roll-out mats that are pegged into place by divers. Once located, a release line is operated to allow the fronds to "float" upwards like strings of seaweed around a metre long. The fronds disrupt the water flow to such an extent that sediment is quickly deposited to cover the mattress, in many cases to the full length of the fronds.

The only real drawbacks with this system are that once installed, the mats are difficult to remove, and that they need to be installed using divers. However, the frond mats can be fixed to concrete mattresses, which can be installed by ROV. These are particularly effective but again they cannot be easily removed.

Rubber disposal

Finally, tyre mattresses are a relatively new innovation and help recycle the ever growing mountain of used vehicle tyres. These are interlinked and when laid on the seabed quickly become filled with sediment which not only keeps the tyres in place but also adds to the protection of the underlying asset.

Ultimately, operators should remember that out of sight should not mean out of mind. The cost of repair is substantial. Initially there are the direct costs associated with vessels, plant, specialist equipment, personnel, repair joints, cable and lost revenue, but also the hidden cost of reputation damage, which will have an impact on customers, shareholders and insurers.

George Birkett is resources manager for UK independent marine services provider Offshore Marine Management

.png)

.png)