Driven by political compulsion and falling subsidies, the offshore wind industry is under intense pressure to reduce its costs. In Europe, the aim is to reach the magic figure of EUR 100/MWh by 2020 or thereabouts, down from around EUR 150-200/MWh today. While no one denies it is a huge challenge, most in the offshore sector seem optimistic that this goal can be reached. To do so will require every link of the value chain to play its part, from turbine manufacturing to final decommissioning. Every aspect will have to be examined to see how even tiny improvements in performance combine to make the difference.

There are, of course, some crucial elements on which almost everything else depends. First and foremost is solid political support, giving long-term visibility, stable regulations and simple permitting procedures. Sufficient volume is also needed, allowing industries to invest and achieve economies of scale, to innovate and develop serial production.

Innovation can bring about 20% of cost reduction, according to Jan Matthiesen, offshore renewable technology acceleration manager at the UK's Carbon Trust. Larger, more efficient turbines should bring savings in installation, balance of plant and operation-and-maintenance (O&M) costs, in addition to higher yields. New foundation designs, installation techniques and electrical systems will also contribute. Areva and shipbuilder STX France, for example, have adopted an integrated approach to designing an optimised jacket foundation for Areva's 5MW and 8MW turbines. This will save significant amounts of steel, says Philippe Kavafyan, director for France of Areva's offshore wind division. Bigger turbines will also cut installation times, making a 30% cost reduction in this area achievable, he says.

Streamlining supply

Offshore wind's supply chain provides room for further improvement. Volume and visibility again are key to boosting competition. Greater standardisation, leaner manufacturing and more streamlined certification will also drive down prices. "There are only three suppliers of export cables in Europe," says Jacopo Moccia, head of political affairs at the European Wind Energy Association (EWEA), by way of example. While the manufacturers could ramp up production, they worry about lack of visibility in the market, Moccia adds.

By the same token, there is a shortage of experienced cable-installation providers, meaning developers pay a premium to secure the right expertise. "Cabling, which makes up 10-15% of the capex of a project, is often one of the elements that gets left to the end [of the planning process]," says Thierry Soudet, director of marine renewable-energy projects at French maritime services group Louis Dreyfus Armateurs. "Yet 75-80% of insurance claims arise from cabling," he adds.

The Carbon Trust is also working on inter-array cables, aiming to double the voltage levels from the present 33kV to 66kV. "Higher voltage means lower losses and more power through the same cable," says Matthiesen. The Carbon Trust estimates that higher voltage arrays could reduce the cost of offshore wind by 2%, halving the amount of cabling and substations required. Various countries are also looking at building meshed grids with offshore hubs, where several facilities connect to a shared offshore substation, thereby cutting costs and reducing risk for developers.

For Frederic Petit, business and marketing director of Siemens France, turbine installation is a key driver. At the London Array project in the UK, equipped with 175 Siemens turbines, the company cut the time taken to install a machine from 22 hours to six through careful management and having the right vessels available at the right time, Petit says. Size also helped, as the 630MW project was big enough to allow a certain industrialisation of the process.

While the number of vessels capable of turbine installation has grown significantly in recent years, there is still a shortage when it comes to foundations. In either case, meticulous planning is essential to ensure these massively expensive vessels are used with optimum efficiency. Innovations in both vessel design and installation techniques for foundations will help. For example, various companies are testing drilling and vibratory driving techniques instead of traditional pile-driving. Some of these promise not only to be quieter, but also faster and less weather dependent, giving an all-important longer working window.

Offshore O&M is still in its infancy, yet represents up to 25% of its levelised cost of energy, including lost production. "There is a large potential to improve yield and availability," says Peter Eecen, programme development manager wind energy at the Energy Research Centre of the Netherlands (ECN). In a study of wake effects, for example, ECN showed that, rather than trying to produce as much energy as possible from every turbine in an array, it is possible to increase the yield of the project by up to 3% by using innovative management of each row of turbines, while also causing less wear and tear and therefore reducing the need for maintenance, says Eecen.

Equally important is what Eecen calls the integrated design of all aspects of the wind farm, from maintenance vessels to support structures. Better monitoring and control strategies to avoid unplanned maintenance, more reliable components and faster, more appropriate vessels can lead to sizeable cost savings over the project lifetime. Research by engineering consultancy the Fichtner Group and business consultants Prognos shows that O&M costs can be cut by up to a third over the next decade, using strategies such as sharing vessels and logistics infrastructure.

Steep increases

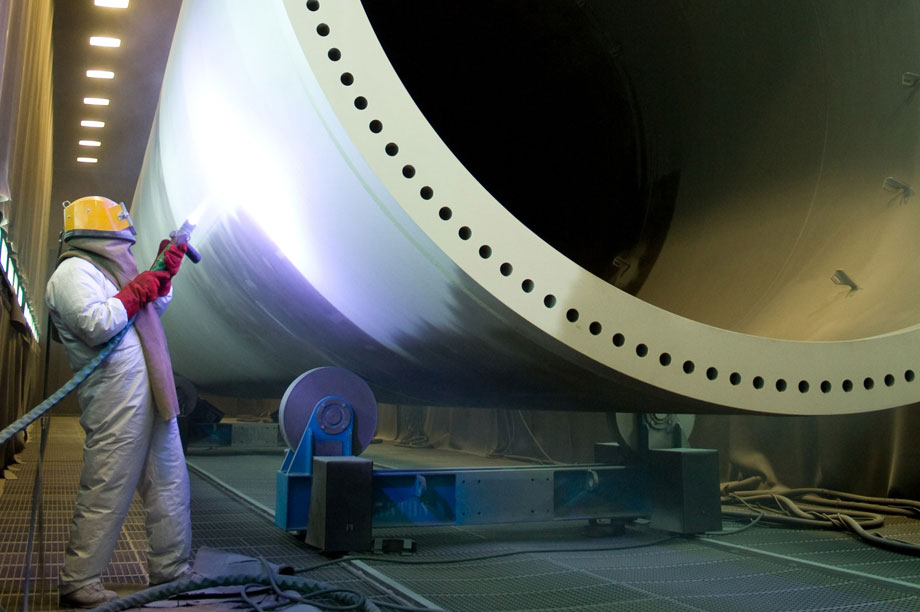

At a more detailed level, Francois Piquet, CEO of Ouest Normandie Energies Marines, which promotes marine energies in France's Basse-Normandie region, signals how steeply prices increase as maintenance goes offshore. To paint one square metre of a turbine onshore costs around EUR 50, he estimates, whereas offshore it can amount to EUR 5,000, taking into account the boat hire, travel time, weather constraints and so forth. "The first company that designs a paint that lasts ten times longer will make a fortune," Piquet notes.

But perhaps the single most significant move to improve offshore wind's price competitiveness will be to reduce the cost of finance. Because offshore wind is a relatively new market, which is not well understood yet by banks and other financiers, lenders demand several additional percentage points of return on their investment, notes Antoine Rabain, director of energy, resources and green technologies at Indicta, a French business development strategy consultancy. Once they feel more comfortable with the risks — or the risks are reduced — this will immediately lead to lower premiums that will have a positive impact on the levelised cost of energy.

For example, says Rabain, French banks demand over 15% return for lending to projects in the first offshore tender, but the rate would normally be around 8-12% for a private energy infrastructure project. Assuming a cost of EUR 220/MWh, cutting the rate of return from 16% to 12% would bring the cost down to EUR 190/MWh, he says.

Finding more innovative funding structures, including engaging more public money to attract commercial lenders, can also play a role. So too will the gradual process of de-risking that comes with greater experience, as the sector becomes more mature and lenders are better able to analyse the potential problems. "De-risking is key," says EWEA's Moccia.

"The first risk factor banks mention is policy, then grid connection, then technology."

Which brings us back to the fundamental need for a stable framework and a long-term vision for the industry.

.png)

.png)