This was confirmed by Francis Fuselier, general counsel North America for Gamesa. Grid congestion in the area is almost certainly a major factor, said an analyst.

Gamesa was left holding Pocahontas Prairie after a deal collapsed. It was to sell the project — and three others in the US — to the Canadian utility Algonquin Power & Utilities Corp in a 480MW deal. Pocahontas Prairie was commissioned in 2012. It is a merchant project, selling its power to the open market, and has no power purchase agreement.

In late November 2012, it had emerged that Algonqin had agreed to compensate Gamesa for pulling out of the Pocahontas Prairie purchase by increasing its stake in the three other projects, from a previously agreed 51% to 60%.

Algonquin said in a press statement: "Algonquin and Gamesa have agreed to defer the acquisition of any interest in Pocahontas Prairie pending Gamesa satisfactorily contracting the output of the facility on terms that meet Algonquin's risk-return profile," the Canadian company said in a press release. All four projects are merchant projects.

Grid congestion

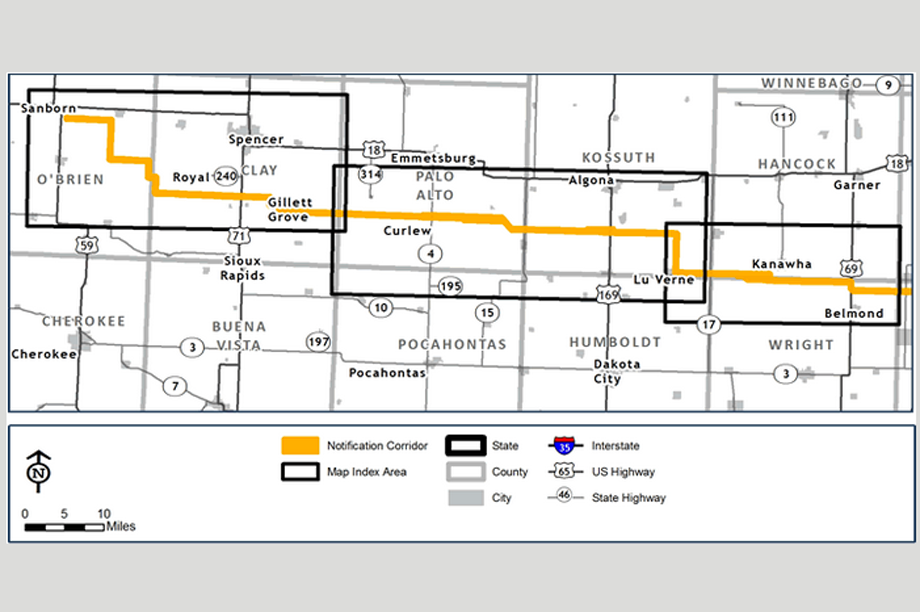

Worsening grid congestion is a well-known problem for north-west Iowa because of the growing number of wind projects, said Beth Soholt, director of Wind on the Wires, an advocator of wind-friendly transmission in the northern Midwest.

Soholt, who sits on an advisory committee for the Midwest Independent Transmission System Operator (MISO), which oversees transmission across nine states in the northern Midwest, also noted that project sales are highly complex and can be held up by multiple factors.

Three major transmission lines in and near north-west Iowa are planned, she said. "As a general matter we think the new transmission should be a good thing," said Gamesa’s Fuselier. Congestion in the region will be eased considerably once the Brookings transmission line, in southern Minnesota, and the Badger-Coulee in Wisconsin — two of MISO’s multi-value projects — are completed in order to help uncork the region’s burgeoning wind power. They are on schedule and will be online in 2015.

Clean Line’s Rock Island’s 35GW high-voltage direct-current line, originating near Pocahontas Prairie, will be finished in about 2018. Clean Line president Mike Skelly said that — as a HVDC connection — tying into the line usually only makes sense for new projects unless they wheel power through the alternate-current grid.

A major hurdle to Gamesa’s sale of Pocahontas Prairie is that a financial hedge had not been secured for the project, said Amy Grace, head US wind analyst for Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF). She reviewed an Algonquin presentation from March 2012 for potential investors that was sourced online by “uåX˜äŠÊ˜·³Ç.

A financial hedge is when an investor provides a buffer against fluctuating electricity prices by paying the project owner a certain amount per megawatt hour if the selling price exceeds a certain agreed-upon range. If the electricity price falls below that range, the project owner must instead pay the hedge provider.

"I am 100% confident" that Gamesa and APUC had not secured a financial hedge, she said. "They could not get a hedge because of congestion in those lines [in north-west Iowa]." Gamesa would not comment. Merchant wind projects try to get a financial hedge because, by definition, they have no power purchase agreement (PPA) with a utility. MISO power prices have been about $30-$32/MWh. Pocahontas Prairie’s power sales pricing hub is the MISO - MinHub.

The Algonquin presentation describes a tax equity investment in the four projects by JP Morgan and Morgan Stanley of $360 million. The three other projects are the 200MW Minonk in Illinois, the 150MW Senate in Texas and the 50MW Sandy Ridge in Pennsylvania, which all have financial hedges.

Then in November 2012, Research Views reported that Citigroup had agreed to buy Pocahontas Prairie for US$53 million. The proposed ownership interest was not disclosed. Typically a commissioned project would be valued at about $2 million/MW, said BNEF’s Grace. Neither Citigroup, which presumably has a higher risk appetite than Algonquin, nor Gamesa commented before deadline.

The presentation said: "Upon acquisition, JP Morgan Energy Ventures Corporation provided a commitment for long-term, fixed-price power sales contracts with a weighted average life of 11.8 years (Minonk and Sandy Ridge 10 years, Senate 15 years)." Algonquin has said it expects to own the three projects fully by early 2014.

.png)

HR.jpeg)

.png)